Gently guiding the (machine) learner

====================================

1. Why should we be interested?

Often in Data Science and Machine Learning we are constrained by a lack of adequate labelled data. We have the tried-and-tested Supervised Learning (SL) algorithms, we have an idea of what type of task and output we would like to see, we can even imagine that glorious insight we’d gain from applying our Neural Nets and Decision Trees, BUT we just don’t have the (labelled) data.

Generating labelled data sets is time-consuming, expensive and ludicrously tedious. Imagine having to go through several hundred thousand photos and tag them with the number of pine trees they contain. You’d get bored very quickly. Now imagine if you had to read through hundreds of thousands of lines of text, labelling them with whether the sentence is in active or passive voice. On top of being bored, you’ll get sloppy at some point, so an additional labeller will probably be needed. The problem becomes worse for complex data points, such as long legal documents or health records. For any organisation trying to leverage its data, the cost of this (in terms of time, money and, frankly, morale!) will quickly ramp up! So instead of using SL, we can turn to a form of Semi-Supervised Learning, specifically, Active Machine Learning. 2. What is Active Machine Learning? The purpose of Active ML is to supply the smallest necessary amount of labelled data to produce a robust learner while minimising human intervention. The human labelling is restricted to those cases where it has the maximum usefulness. Now some questions arise immediately from that statement:

- How do you determine the “smallest necessary amount”?

- Which data should go into that amount?

- What are we defining as “usefulness”?

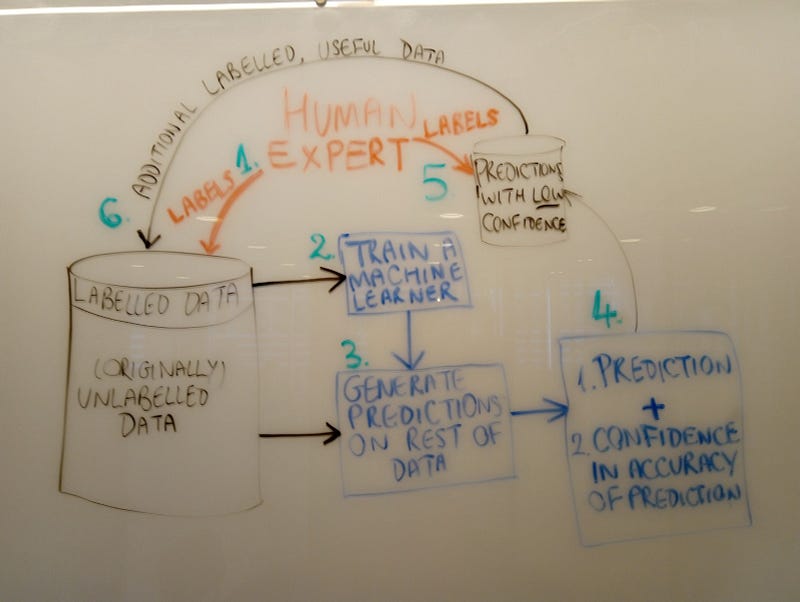

I’ll delve deeper into those issues in section 3. Figure 1 shows the general steps in active ML. The green numbers represent our steps detailed below:

-

The human expert only labels a subset of that data (say 10%; the individual steps are shown in green). This cuts down massively on labelling time. Let’s refer to this initial labelled data as the seed data.

-

We train our machine learner (which could be ANY type of algorithm suited to our task, be it regressor or classifier) JUST on the seed data.

-

The now trained learner generates predictions on the rest of the data set and provides a value of how confident it is for each of its predictions.

-

The learner returns the predictions with the lowest confidence ratings to the human domain expert (kind of like a student going to a teacher with their homework saying “I wasn’t really sure how to do these…”).

-

The human expert only labels these low-confidence data points.

-

Finally the additionally labelled data is fed into the labelled data set and, along with the seed data, is used to retrain our machine learner.

A lot of the problems arise in Step 1, where we select our seed data. Before addressing that, let’s go through an example.

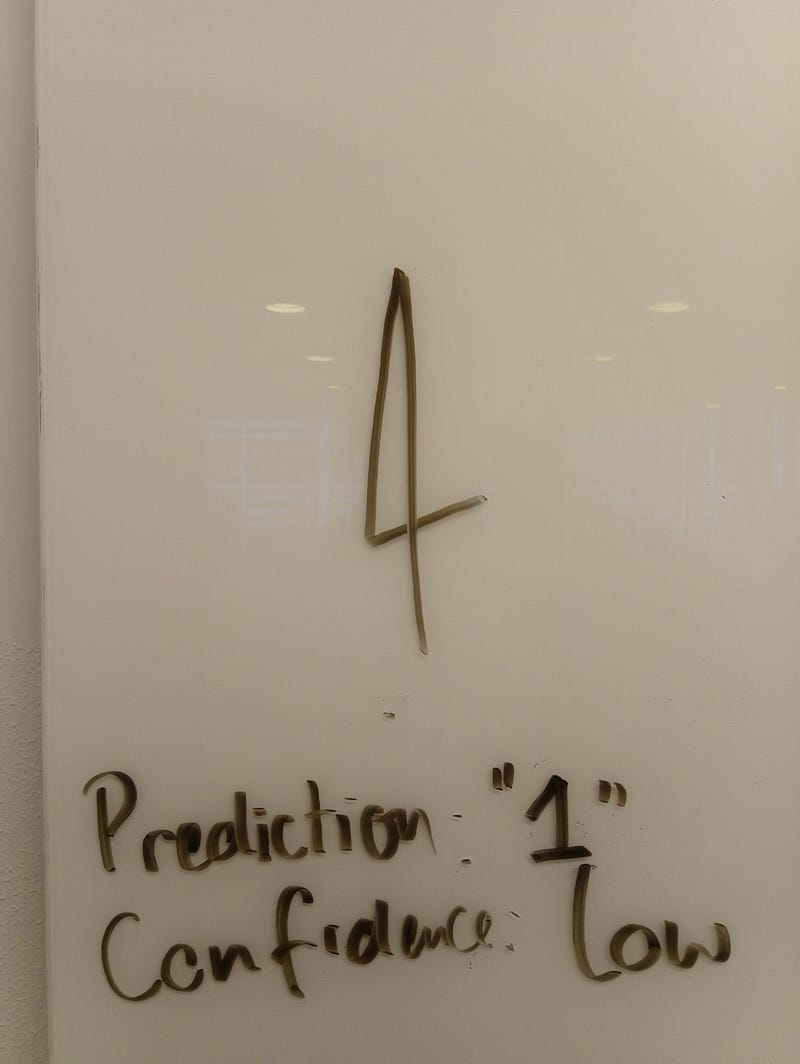

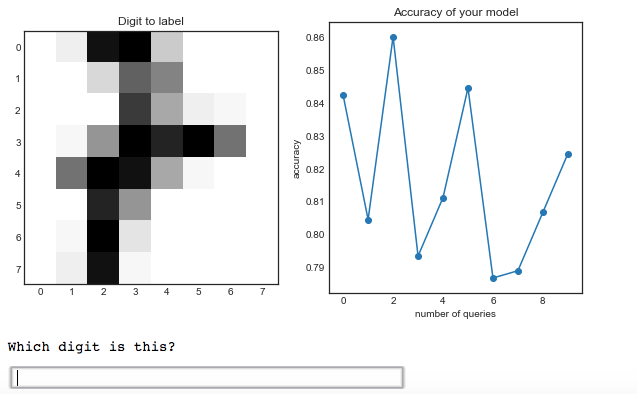

Imagine you’re training a classifier on the MNIST handwritten digits dataset (a collection of pixelated images of single digit numbers from 0 to 9). Suppose that we lost all the labels for this data. We could just the then you would train your learner on a subsection of the data that was labelled. It is useful to think of the low-confidence data points as being highly discriminant - they are very good boundary cases that test your learner’s comprehension of the data. Then, when our learner makes predictions on the rest of the data, it will return us the predictions with the lowest confidence, as shown in

In Figure 3 you can see an example of what this would look like in a Notebook (I used the standard example code for modAL, an Active Machine Learning library built to be compatible with Scikit-Learn).

3. What are the limitations? How do you determine the “smallest necessary amount”? Which data should go into that amount? What are we defining as “usefulness”?

This questions is domain- and data-specific. If you apply both standard supervised learning and AML to a dataset, as you increase the amount of initial labelled data supplied, your accuracy will increase in both cases. However, if the assumptions of AML are robust, then the accuracy curve will be steeper for the active learning process than for the standard supervised learning technique. In this case you should determine the relative costs of labelling more data and seeing what the uppermost limit on data labelling would be. There is no definitive answer (yet!) to this question, so empirically trying out the method on any previously labelled data sets to determine a cost-optimal threshold would be a good way to start. This is an area of active research: ideally you need to provide an initial data set that is significantly representative of your total data set. Any bias in your initial selection will have significant repercussions in the testing stage, which is a considerable drawback of active learning. A pseudo-random selection from the data (as I have done with the MNIST dataset above) seems promising, but does not guarantee representativeness.

How useful would this row of data be to our learner if it were labelled? Active learning involves the machine choosing which instances to send back to the human (teacher). There are a variety of ways our learner can be set up to choose the most useful data to have labelled, normally based on the learner’s confidence, e.g. least-confidence (querying about the instances which the learner is least confident of in its prediction); margin sampling (chooses instances where the classification margin is the narrowest); query-by-committee (a set of different models are trained on the data and the instances where the greatest disagreement occurs are deemed most useful).

There is still a lot unknown in AML, most significantly the fact that we often don’t know in advance if a particular dataset or type will benefit from this semi-supervised approach. Nevertheless, the literature survey [1] suggests that there are some areas of significant success, especially within Natural Language Processing (one example of AML being used successfully in Named-Entity-Recognition here).

4. References

[1] Olsson, Fredrik (2009) A literature survey of active machine learning in the context of natural language processing. [SICS Report]. Available at: http://eprints.sics.se/3600/ [accessed on 30.12.2019]

[2] Deep Learning Scaling is Predictable, Empirically; Hestness, J. et al, arXiv:1712.00409 [cs.LG]. Active (Machine) Learning - Computerphile. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ANIw1Mz1SRI. [accessed on: 30.12.2019]

[3] The code snippets were completed using modAL:

@article{modAL2018,

title={mod{AL}: {A} modular active learning framework for {P}ython},

author={Tivadar Danka and Peter Horvath},

url={https://github.com/cosmic-cortex/modAL},

note={available on arXiv at \url{https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.00979}}

}